Some pictures about Gaza, and how and why I made them

Over the period January, 2024 through September 2025, I made several pictures about Gaza. The first three, completed by June, 2024, form a trilogy: Oshkosh Has the Right to Defend Itself; Behind (for Hind Rajab; and Veto (Merry Xmas from US), now hinged together as a triptych. I spent most of July 2025 making the fourth: Geography of the Genocide (for Francesca Albanese), and September 2025 making the diptych The Canon of Hussam al-Masri (Self Portrait with Martyrs). I began them out of frustration and despair, something to keep my hands busy. I here describe what they are about and how I came to make them.

Left: Oshkosh Has the Right to Defend Itself; Center: Behind (for Hind Rajab); Right: Veto (Merry Xmas from US). UV photopolymer resin and powdered pigments (house dust for center image) on gessoed board (glass mirror for center image). All three prints, John Beaver 2024.

Veto was both the first and the last in the 2024 trilogy. In January 2024 I made a digital picture from a scanned, paper negative, using one of my own sort-of invented, lo-fi photographic processes. I apologize that I must now talk a little about my own methods, but they are an important part of what I did and why I did it. I annoyingly refer to this particular technique as “ephemeral process,” but it may also be called accelerated lumen. When used to make direct shadow prints (photograms), it allows me to work in a tiny space in the basement. It uses no harmful chemicals, and both setup and cleanup are quick and easy. The direct result is a paper negative with a lot of physicality and expressiveness. Somewhat ironically, however, the only good way to make a positive from the still-sensitive-to-light negative is to capture it digitally with a scanner. The end product is thus a strictly-virtual digital image.

Veto (Merry Xmas from US), 2024 John Beaver. Three-layer CMY new resinotype (UV photopolymer resin and powdered pigment) print on gessoed board, 12''x9'' (unframed size).

Since exposure times are only a few minutes long, it is possible to go from concept to completed image in less than one hour. A darkroom is unnecessary; I compose the exposures on a small table, working quickly under dim, indirect light from an ordinary light bulb. The composition of such a photogram exposure comes down to arranging objects on the paper surface (or on a sheet of glass holding the paper flat), positioning the light source so as to control the geometry of the shadows, and then turning on the lamp. The paper darkens visibly, and so the exposure is usually controlled by eye.

I am always on the lookout for suitable photogram objects, and my collection is now up to several boxes, labeled with categories such as ``Small Nature'' and ``Transparent Containers.'' The live 30.06 and 0.38 shells that appear in Veto (Merry Xmas from US) were both found (in separate incidents) in Appleton, WI parking lots. There is some peace in the process of selecting objects and arranging them quickly on the light-sensitive paper while imagining what the final picture might look like. Because of the calming nature of this physical act, I often turn to this process when I am otherwise at a loss. Such was the case for the image, made in early January, 2024, that is the primary source for Veto (Merry Xmas from US). I toyed with submitting the image for publication, but I had second thoughts. Although the act of making it was helpful to me personally, I feared it attempted to depict the direct experience of the people of Gaza, something I am in no position to do.

In response to my misgivings about the image from January, two months later I made Oshkosh Has the Right to Defend Itself, using my new resinotype photographic printing process. This technique uses a thin layer of UV-sensitive photopolymer resin to stick powdered pigments directly to almost any hard surface in order to make a permanent print. All three of the prints in this Gaza Trilogy are new resinotypes.

Oshkosh Has the Right to Defend Itself, 2024 John Beaver. Three-layer CMY new resinotype (UV photopolymer resin and powdered pigment) print on gessoed board, 12''x9'' (unframed size).

This time I tried to keep it local, choosing as the focus the grounds of Oshkosh Defense, LLC, whose headquarters (and one of its factories) are only a 15-minute trip down the highway from our home. The print was made from a color image screen-grabbed from Google Earth. It shows a snapshot of part of the grounds, with rows of completed military trucks ready to be shipped off. The color image was separated digitally into three black-and-white images, one each for the primary printing colors cyan, magenta, and yellow. These images were then printed with an inkjet printer onto transparency film, and the transparencies used to expose the photopolymer resin three times, each time dusting it with a different powdered pigment to build up a full-color picture. Before exposing each layer, however, I arranged the cake-baby photogram objects on top of the glass holding down the transparency. More information about Oskosh Defense and its role in the war on Gaza can be found here.

Veto (Merry Xmas from US) was printed in June, 2024, using the same three-color new resinotype process. The three transparencies for the print were made from a cropped version of my January digital image. The look of this print is markedly different from the digital image. Re-imagined in this way, and accompanied by its title, I feel a little better about it.

Regarding Behind (for Hind Rajab) in particular, and the commitment to make a trilogy in general, The Night Won’t End: Biden’s War on Gaza was the concrete block that broke the camel's back. I'd already read much about Hind Rajab, but I had not really let it in. As a rule I stick mostly to print, an attempt to keep my head clear. I deal in visuals and know full well their often-undeserved power, and I thus mostly avoid them regarding the news, so as not to be jerked around. At the urgings of Jeffrey St Clair in his Gaza Diary, published weekly in Counterpunch, however, I did fortunately watch this amazing documentary by Kavitha Chekuru and Laila Al-Arian. Seeing these unadorned and matter-of-fact testimonials, sometimes rendered more powerful by a delivery that is simultaneously flat and barely-in-control---surely arising from trauma---what can one do but do something?

Behind (for Hind Rajab), 2024 John Beaver. New resinotype (UV photopolymer resin and house dust) on glass mirror, direct contact print from in-camera paper negative, 10”×8” (unframed size).

I made Behind with the same new resinotype process as the other two, but it is printed instead onto a thin mirror. Many kinds of powder will work for this process, and for various reasons I have made prints in the past not only with traditional artist pigments, but also with cinnamon, achiote, turmeric, beet powder, blue spirulina, and ground-up Tylenol. In this case I used dust from our house, collected with a soft brush from shelves, ductwork, and the top of the refrigerator. House dust is primarily flat, microscopic flakes of skin---in this particular case my own, that of my wife and partner (also named Valeria), and our cat Tobias. Perhaps there are also some flakes remaining from our dearly departed Boris. The tiny flakes, where they are held by the resin to the mirror surface, scatter incident light in all directions; the mirror itself, on the other hand, reflects light only according to the law of reflection. If illuminated so the mirror reflection misses the viewer, it looks black, while the diffuse scattering from the dust reaches the viewer and so looks bright. The image in the mirror is thus made literally from the shedding of my own skin, and that of my closest companions. You may notice that the edges of the mirror look sharp and irregular. I suppose it is appropriate that the picture is dangerous and could potentially draw blood. The other reason, however, is that I absolutely suck at cutting glass.

I hope that Behind (for Hind Rajab) challenges you to, for at least a few seconds, look in the mirror and be Hind. And then do something to the best of your ability, even if it is only possible to raise your left arm in anger and lament. But it challenges me even more; the picture is, after all, made partly from former versions of my own self. It is hard for me to look into this mirror. I see what I have not done.

Behind (for Hind Rajab), as photographed in a room with lights.

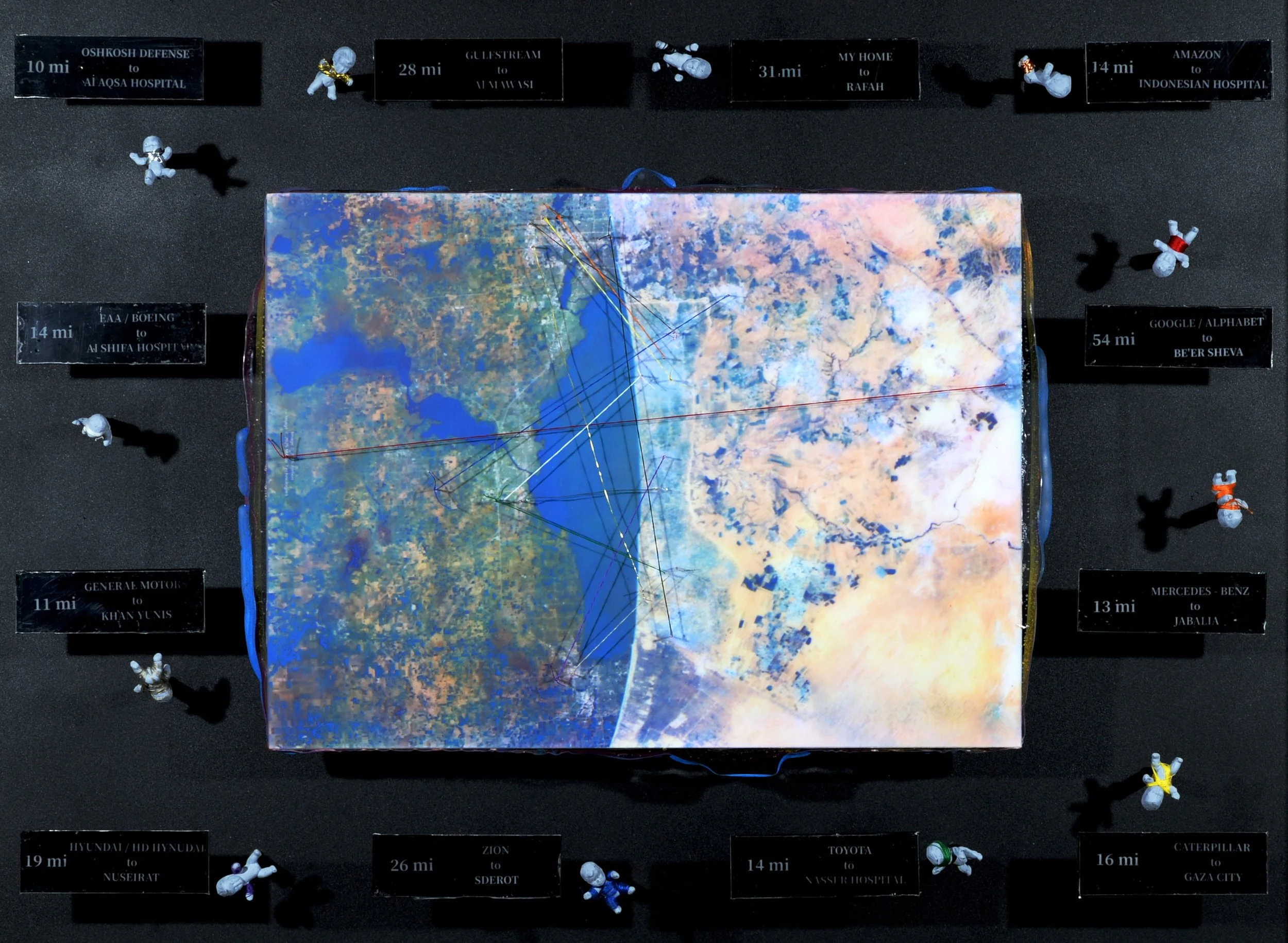

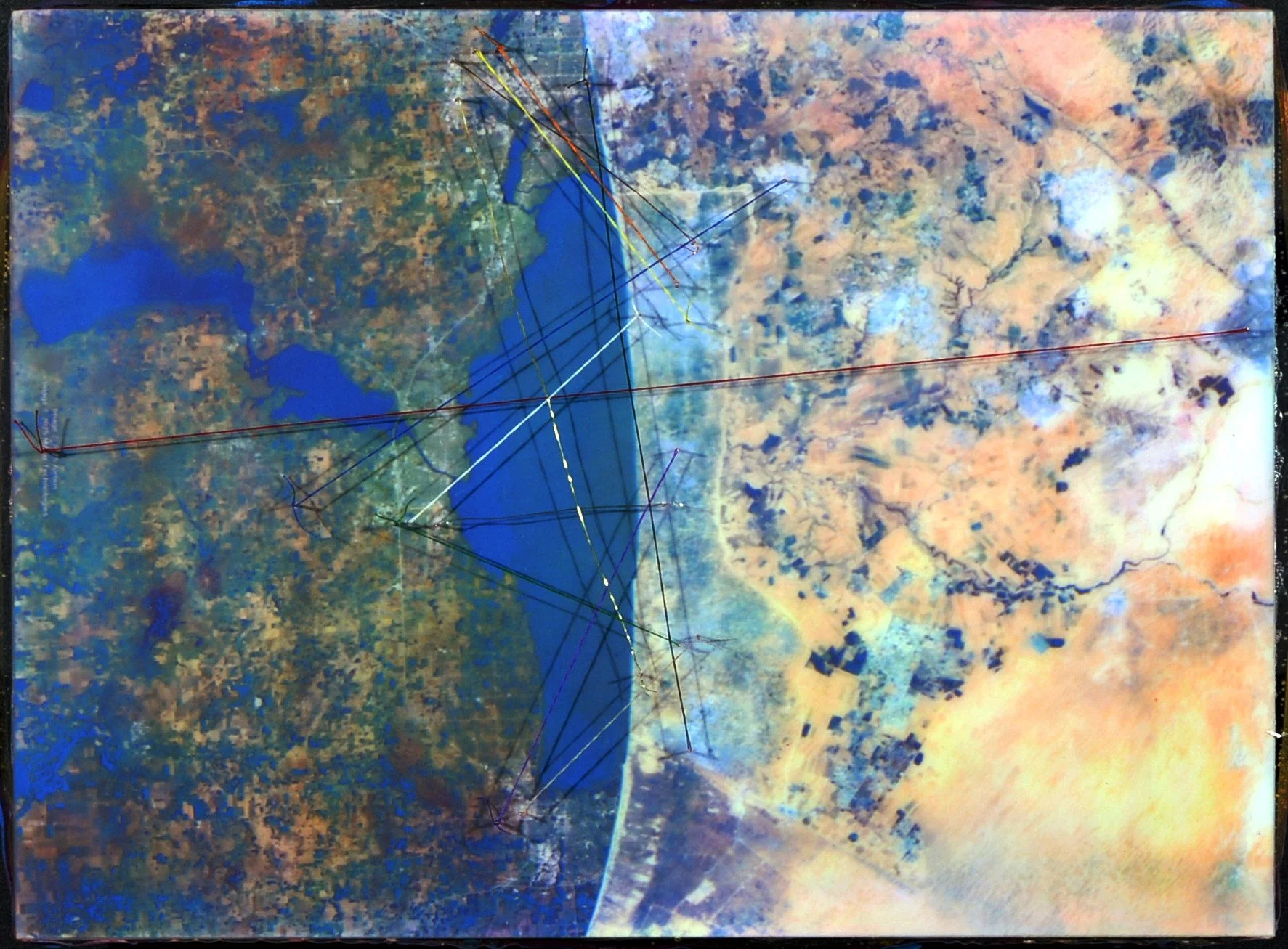

I began Geography of the Genocide (for Francesca Albanese) just before the release of the UN Human Rights Council report by Francesca Albanese, "From Economy of Occupation to Economy of Genocide". Her report documents in detail the active and passive collaboration of dozens of corporations and institutions in the genocide against Gaza. Taking a Northeast Wisconsin perspective, I compiled a map from Google Earth, cutting and pasting Gaza onto the Lake Winnebago region (which includes my home), with both parts set to the same distance scale.

A “key” surrounds the central print: cake baby figures are wrapped in colored thread, corresponding to threads stretched across the map between sewing needles embedded in Wisconsin on the left, and Gaza on the right. The label for each key tells the distance between the two locations in this alternate universe where we can't ignore what is happening thousands of miles away. The central print is a 3-layer new resinotype made with ground Conte and UV photopolymer resin on gesso board, with sewing needles, colored thread and metal wire.

The labels for the key are new resinotype prints onto glass microscope slides, using ground acetaminophen (parecetamol) pills as the white pigment (each is backed by a second slide, painted black). The conditions in Gaza’s few remaining hospitals are so dire that analgesics are sometimes resorted to where general anesthesia should be used, even for extreme cases such as amputations.

I had to work out many technical details to make Geography of the Genocide, but wrapping and positioning the 12 figures was the most difficult part, and I saved it for last. Although I would never divulge the names without the active collaboration of the families, each figure portrays a specific child. I gathered the names and their stories from news reports; each was killed at an age of less than 18 months.

In September of 2025, I made a diptych in response to the killings of journalists at the al Shifa Hospital on 8/10/25 and Nassar Hospital on 8/25/25. The Canon of Hussam al-Masri (Self Portrait with Martyrs) also takes inspiration from Self Portrait as a Female Martyr by Artmesia Gentileschi. In the attacks on the Nassar Hospital complex, what Israel claimed was a “Hamas camera” was actually the Canon camera of slain Reuters journalist Hussam al-Masri. The Canon of Hussam al-Masri (Self Portrait with Martyrs) is two 12” x 9”, three-color ground Conté new resinotypes on gesso board, but with a 4th layer of red ochre for the feather photograms. The self portrait is printed with white Conté onto the back of an old stage light condenser lens (and then over-painted with a layer of black gesso). The pictures were edited from news story press release photos, with the backgrounds (of the two hospital complexes) screen-grabbed from Google Earth.